Image Source : Colorado State University

India’s mental health crisis is not only an intangible crisis but an overdue economic and social disaster. With almost 200 million Indians—14% of the population—afflicted with mental disorders, the scale of the crisis is enormous. But India spends only 0.05% of its GDP on mental health. It means that out of the nation’s total economic output, a fraction—a paltry five paise for every hundred rupees—is spent on mental health facilities, such as hospitals, awareness generation, rehabilitation, counselling, and preventive treatment. Not only is this low in terms of numbers but also relative to the world: while the WHO suggests that nations spend at least 5% of their health budget on mental health, India spends barely about 1% of its health budget on this area. Most countries spend between 5% and 18% of their healthcare budget on the subject.

A scan of the last five years reveals a sharp stagnation in trends. In the Budget of India for the fiscal year 2019–20, the Union Budget allocation for the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) was ₹40 crore, which has hardly increased since then—falling short of even keeping pace with inflation. Much of the mental health spending is concentrated in the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) in Bengaluru, leaving little to expand services across states. The share of GDP spent on mental health has remained around 0.04–0.05% throughout this period, reflecting that there has been no real increase in spending despite the rising incidence of depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. This has the implication that demand for services has grown substantially but the state government outlay has actually remained static, so increasing the gap between need and availability.

The imbalance between the demand for healthcare and the level of investment leaves a massive deficit in the public health system of the country. The cost to the economy is equally dire: an estimate puts the cost of untreated mental illness in India between 2012 and 2030 at more than USD 1 trillion, which is approximately 2.5% of India’s GDP every year. Mental illness, in short, is not only a humanitarian issue but also an economic threat to India’s vision for long-term growth.

Perhaps the most publicly apparent symptom of this crisis is suicide. India had 164,033 suicides in 2021, an all-time high and an increase of 7.2% from 2020. Suicide has become the number one cause of death among 15-29-year-olds, claiming 17.1% of deaths in this category, second only to road accidents. Especially heartbreaking is that the over 42,000 suicides by daily wage earners, who lived with permanent economic uncertainty, represented almost 25.6% of the total. For those who live on the edges of life, any slight dislocation is fatal. This trend reflects a structural reality: measures that require the most vulnerable to “make time” for self-care will fail. To instruct a daily wage earner to “sleep more” or a corporate big shot to “meditate daily” is tone-deaf, because both lack discretionary time and energy to spare for these luxuries. Mental wellness strategies only work when they organically become part of workers’ lives and deliver immediate, material, and socially valued payoffs.

This is where current mental health interventions in India go wrong. The National Mental Health Programme and Tele-MANAS, for instance, offer access and infrastructure but never get off the ground because they don’t tackle stigma or everyday realities. Corporate wellness programs are shunned by workers because they fear that taking part will label them as weak, and informal workers, already stretched, consider outside interventions utopian distractions. What they need is not another sermon about self-care but a re-engineering of incentives so that workers actively adopt mental well-being because it feels good, it’s essential, and it’s even status-boosting.

The challenge lies in finding out who will finance these interventions and why they would do it on a voluntary basis. For day-wage and low-skilled laborers, initial financiers must be employers in the unorganized sector, municipal governments, and the corporate social responsibility (CSR) wings of industries. The return is unambiguous. Employers gain with healthier workers being more productive, absent fewer days, and less likely to have injuries on the premises. International Labour Organization statistics indicate that stress interventions reduce absenteeism by 20–25%. Governments benefit by reducing hospital burdens and achieving localised Sustainable Development Goals like reducing suicide rates. Industries can then use CSR funds to invest in mental health interventions to improve their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) scores, showing tangible social return. To keep expenditures low, interventions can piggyback existing infrastructures: chai-baithaks conducted within Anganwadi centres or ICDS offices, Mobile Wellness Vans deployed across the National Health Mission fleet of mobile health vehicles, and bulk purchases of low-cost herbal stress kits that can be distributed to workers in bulk. The World Health Organization estimates that there is four-fold return in productivity and saved healthcare expenditures for every rupee spent on mental health, making the economics self-sustaining.

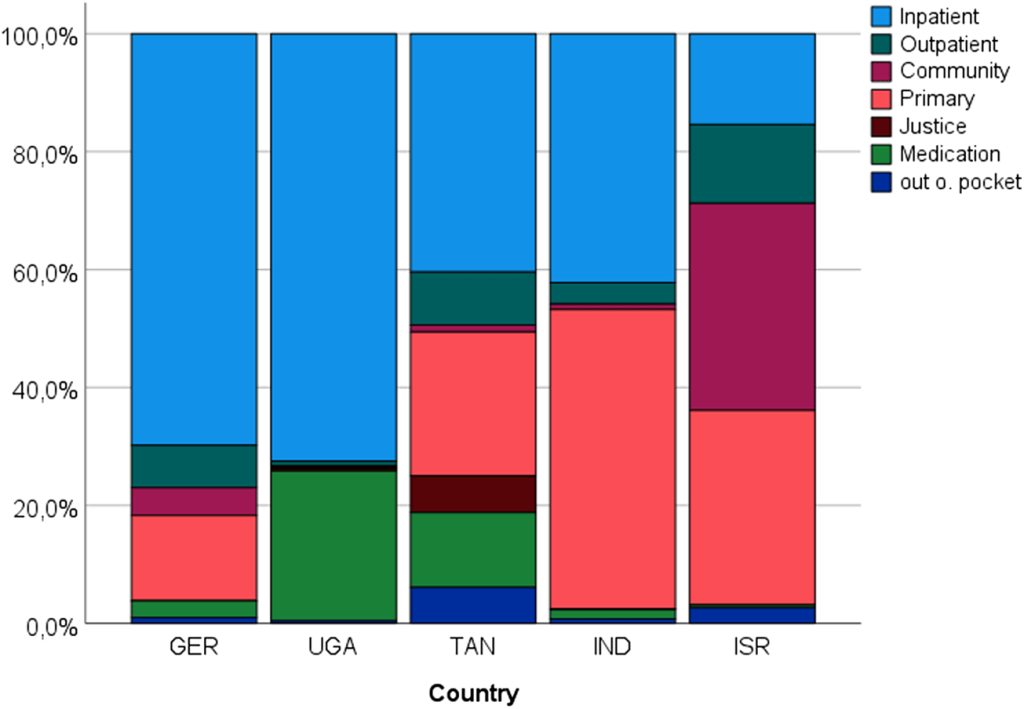

Source: Park A-L, Jez O, Kilian R, et al. A comparison of the costs and patterns of expenditure for care for severe mental illness in five countries with different levels of economic development. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2025;34:e40. doi:10.1017/S2045796025100140

Source: Mental Health Atlas 2020 country profiles (2017 profile for India and Israel), Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.

For corporate leaders, the stakes are different but no less convincing. Here, multinational businesses, insurance firms, and even employees themselves are major co-financers. Deloitte’s studies show that workplace wellness initiatives can yield returns of four to nine times the cost by lowering employee turnover, lowering rates of absenteeism due to illness, and increasing overall productivity. Health insurers have a vested interest in funding such programs because the removal of workplace stress can lower claims for chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Employers, too, may be willing to contribute to the financing of well-regarded wellness programs if these are gamified or attached to other rewards, such as gym memberships. Interventions can take the form of IT-driven reminders for short breaks, digital detox areas within office spaces, or wellness challenges that are gamified and whose team participation results in rewards such as Uber credits or extra days of leave. By making wellness measures a performance metric, organizations secure managerial support while casting participation as a sign of productivity, not of frailty.

At the national level, the government has both the mandate and the capability to enable large-scale adoption. The budget of existing schemes like Ayushman Bharat, Poshan Abhiyaan, and Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana can be leveraged to fund experimental interventions. Scaling up the pilot programmes will require public-private partnerships, impact bonds, and involvement of international philanthropic organizations like the WHO, World Bank, and Gates Foundation. Tax incentives and CSR credits can also encourage corporations to embrace mental health programmes as part of their core social responsibility initiatives.

International experience shows that such coordination of social and economic incentives is successful. In the UK, workplace wellness interventions suddenly saw a surge in take-up once they were reframed as productivity improvements and not health benefits. In Chile, wellness was combined with labor incentives and participation skyrocketed. India can take a cue from such models, tailoring them to local contexts by focusing on cultural comfort and instant gratification. For day-wage laborers, it can be a Mobile Wellness Van with stress-reduction sessions offering free glucose tests or snack vouchers, or chai-baithaks reframed as “Skill and Health Circles” with priority registration for government programs. In urban construction sites, employers can play popular music during breaks to induce short stretch exercises, an inexpensive, culturally acceptable intervention. Providing aromatic sachets or herbal tea sets through food stalls ensures workers experience instant, physical relief while slowly getting them used to talking about mental health.

For corporate workers, wellness needs to be part of the organizational DNA. Digital detox rooms in the office, game-augmented challenges that pay real team rewards, and wellness performance metrics tied to promotion or bonuses all create the environment in which engagement is a natural occurrence. Presenting such programs as part of ESG reporting and CSR compliance provides companies with a strong rationale to invest. By harmonizing the interests of employees, employers, insurers, and regulators, mental wellness programs transition from costly add-ons to value-generating investments.

The bigger picture is obvious: with 65% of Indians under 35, untreated and undiagnosed mental illness threatens to waste the nation’s demographic dividend. The WHO long ago pointed out that for every dollar spent on mental health, four are earned in economic benefit, primarily through productivity and decreased healthcare expenses. If India does not act, the financial and human costs will keep spiralling out of control. But if it can make mental health interventions irresistible—linked to job security, increased wages, and social standing—it can redefine wellness from a personal struggle to a national development priority.

The Indian mental health crisis cannot be addressed by good intentions alone. General advice like “eat a healthy diet” or “sleep well” disintegrate in the face of structural constraints. Interventions are needed that provide immediate value to workers, quantifiable productivity gains for enterprises, cost savings for governments, and industry compliance benefits. Interventions like chai-baithaks tied to work incentives, herbal stress kits sold through street vendors, mobile vans that combine healthcare with rewards, and corporate detox zones connected with bonuses are the future of Indian mental well-being. Engagement will be second nature, not enforced, once mental health interventions shift from a sense of obligation to an opportunity for prosperity and glory. Then, Indian mental well-being will shift from the periphery to the center of its policy debate, not as acts of charity but as part and parcel of strategic thinking.

References

Economic Times. (2022, January 31). The world spends 5 to 18 % of their GDP on mental health, whereas India spends only 0.05% (Font: Dr. Lakshmi Vijaykumar). ETHealthWorld.

World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health in India. WHO India.

National Crime Records Bureau. (2021). Accidental deaths & suicides in India (2021). NCRB via The Hindu / BoomLive / Drishti IAS.

Free Press Journal. (2025, June 26). Suicide among top 2 causes of death for young Indians between 2020–2022.

Sentinel Assam. (2025, April 15). Rising suicide rates in India: A growing public health crisis.